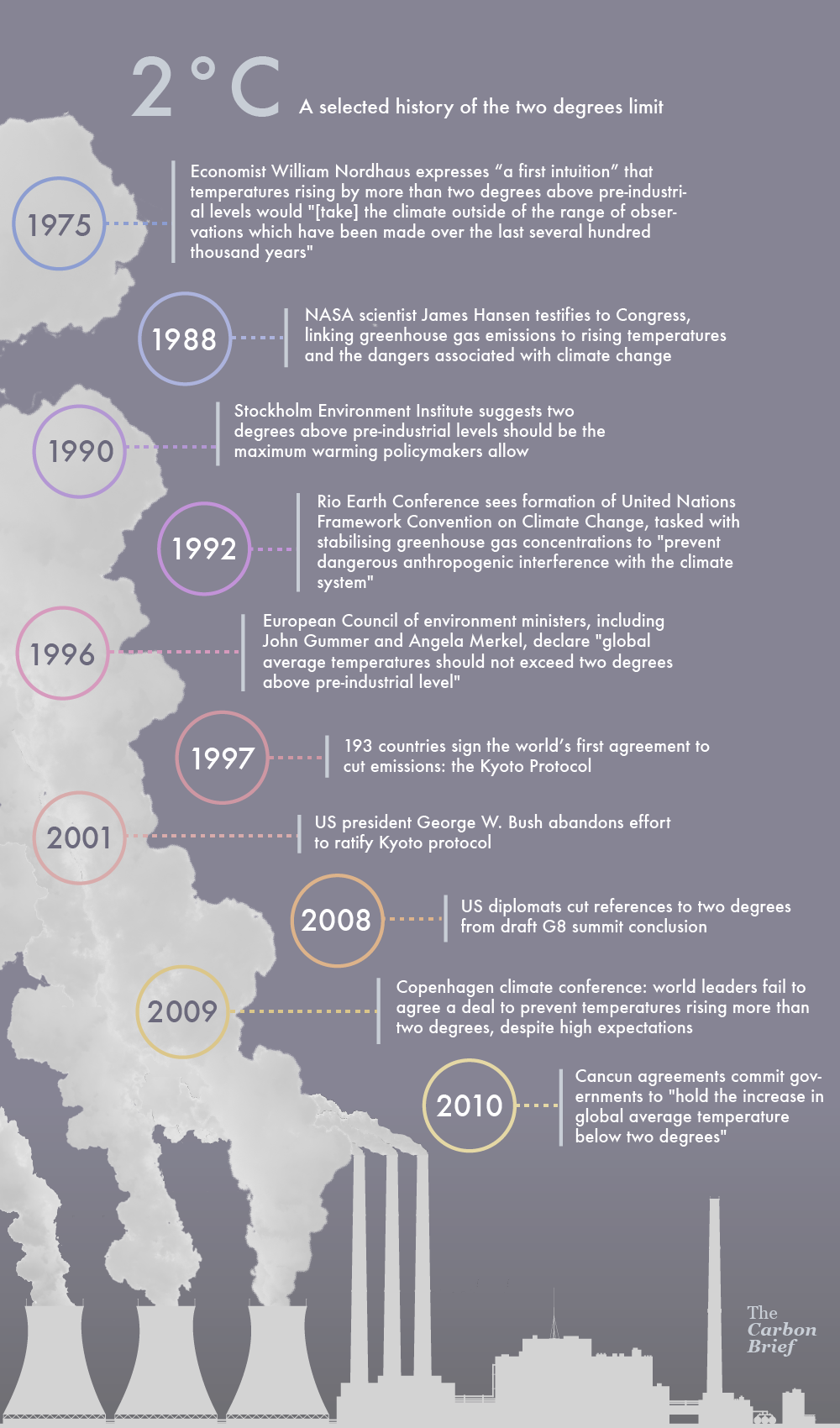

The figure of 2°C temperature rise has been thrown around in talks of climate change almost as much as phrases like "global warming" and "carbon credits". This figure is so prolific that it's difficult to pin down the exact source of 2°C as the limit of global temperature rise, relative to the pre-industrial average, that avoids "dangerous climate change". Below is a nice selection of historical references to 2 degrees.

There was a distinct boom in discussion of climate change, or "global warming" back then, in the late 90s/early 2000s, and 2 degrees featured heavily. Many stakeholders, from scientists to politicians, were talking about climate change impacts under 2°C rise, and what we might do to avoid 2 degrees. Notably, countries were coming together to talk about the environment, with agreements like the Kyoto Protocol and the UNFCCC (United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change).

Even within this month, in 2015, 2 degrees continues to dominate discussions of climate change and impacts. Mentions in current news stories include coral reefs, Antarctic ice shelves, the ocean food chain, wildlife, deserts, weather-related disasters, and most disturbingly, loss of habitability for humans. I also watched this Ted talk recently by climate change and energy researcher, Alice Bows-Larkin. In it, she mentions 2 degrees, and how this commonly discussed limit has left scientists divided into two groups; those who believe we have no chance of surpassing 2 degrees, and those who cling on to the small chance that we can avoid 2 degrees.

As part of this discussion, climate projections and models have looked at how different CO2 levels might affect temperature, and how that could impact multiple areas in the environment and for humans. Just like the 2°C threshold for temperature, some scientists suggest a threshold for CO2 concentrations of 500ppm, and various metres of sea level rise.

So the question remains, can Earth avoid the 2°C change that might render large parts uninhabitable?

According to the IPCC's Fifth Assessment Report in 2013, the globally averaged land and ocean surface temperature between 1880 and 2012 shows a warming of 0.85°C. They state that it is "virtually certain" that globally the troposphere has warmed since the mid-20th century. Alarmingly, they also state that it is "extremely likely" that that more than half of the observed increase in global average surface temperature from 1951 to 2010 was caused by the anthropogenic increase in greenhouse gas concentrations and other anthropogenic changes.They use different scenarios to model changes, and under all but one, global surface temperature change for the end of the 21st century is likely to exceed 1.5°C relative to 1850 to 1900. This does not paint a particularly optimistic picture for avoiding 2 degrees, and they suggest that limiting these changes will require "substantial and sustained" reductions in greenhouse gas emissions.

Interestingly, they also point out that while increasing CO2 will create changes in climate, climate change will in turn affect the carbon cycle, to further exacerbate the increase of CO2 in the atmosphere. In my last post I mentioned balance in the carbon pools, and it is likely that climate change will cause increases in uptake in some pools (ocean) and potential decrease in others (land uptake, although there is a great deal of uncertainty). Carbon, and in particular CO2, therefore plays a hugely important role in whether or not we will be able to avoid 2 degrees.

Since CO2 is cumulative, global emissions of CO2 over time need to be known to understand the effects. The term carbon budget was coined as a way to predict the amount of CO2 emissions we can emit while still having a likely chance of limiting temperature rise by 2°C. A report in 2013 by Carbon Tracker suggests that a carbon budget of 900 gigatonnes of CO2 gives us an 80% probability of avoiding 2 degrees. This means that a large amount of fossil fuels are "unburnable", and the carbon budget is particularly constrained after 2050, where, unless we can create negative emissions, only 75 gigatonnes of CO2 can be emitted to give us an 80% probability of avoiding 2 degrees. This is equivalent to 2 years of emissions at current (2013) levels. The IPCC proposed a carbon budget of 1000 gigatonnes of CO2 starting from 2011, that would give us a 66% probability of avoiding 2 degrees. I'll admit when researching these numbers, I slowly felt my optimism dropping. With current estimates and use of about 35 gigatonnes of CO2 a year, we'll likely use up our carbon budget by 2034, thus leading to those 2°C we've been so intent on avoiding. By 2100, we would've reached 4°C warming, which has even more dire impacts. So right now, the outlook for avoiding 2 degrees doesn't look so good.

The one thing that could avert all this is something radical. A study by Peters et al. (2013) claim that "immediate significant and sustained global mitigation" is needed to avoid 2 degrees, with a probable reliance on net negative emissions for the longer term. They found that some countries have reduced CO2 emissions over 10-year periods, through a combination of (non-climate) policy intervention and economic adjustments to changing resource availability. In the UK, shifts to natural gas, therefore substituting oil and coal, have led to sustained mitigation rates in the 1970s and 2000s. Mitigation strategies focus on fuel substitution, efficiency improvements, and look towards the growing technology in negative emissions. Finally, they emphasise that this is a current and pressing issue, as global mitigation efforts need to be put in place as soon as possible, or soon, our efforts will be futile in avoiding 2 degrees.

There's no way we can know for sure that we'll be able to avoid 2°C, but we haven't given up. Just a few days ago, the executive secretary for the UNFCCC, Christiana Figueres stated that "we are not giving up on a 2 degree world", believing that we can develop processes to ensure this. With COP21 on the horizon, there definitely remains some scope for optimism, and Figueres believes the changing energy industry will play a major role. Kevin Anderson of the Tyndall Centre for Climate Change Research echos this sentiment, although he suggests that the IPCC claims that global economic will be unaffected are unrealistic. He suggests that if we are to meet our 2 degrees target, high emitting (and wealthy) countries will need to drastically cut their energy use and overall consumption. Next week I'll be exploring how energy could help us avoid the 2 degrees crisis.